Kruger National Park History

Did you know?

The surface area of Kruger National Park is 7,580 miles² (19,633 km²).

- The park was first proclaimed in 1898 as the Sabie Game Reserve by the then president of the Transvaal Republic, Paul Kruger. He first proposed the need to protect the animals of the Lowveld in 1884, but his revolutionary vision took another 12 years to be realised when the area between the Sabie and Crocodile Rivers was set aside for restricted hunting.

- James Stevenson-Hamilton (born in 1867) was appointed the park’s first warden on 1 July 1902.

- On 31 May 1926 the National Parks Act was proclaimed and with it the merging of the Sabie and Shingwedzi Game Reserves into the Kruger National Park.

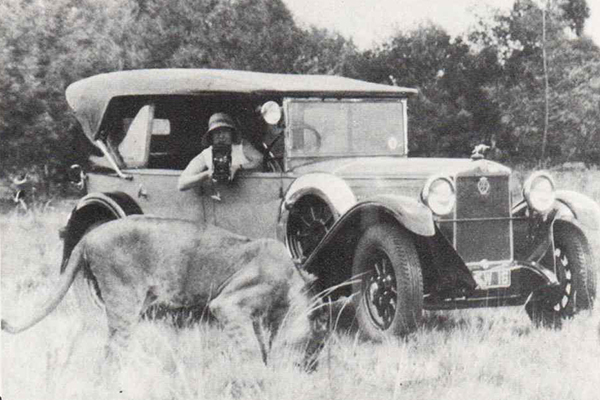

The first motorists entered the park in 1927 for a fee of one pound. - Many accounts of the park’s early days can be found in the Stevenson-Hamilton Memorial Library.

- There are almost 254 known cultural heritage sites in the Kruger National Park, including nearly 130 recorded rock art sites.

- There is ample evidence that prehistoric man – Homo erectus roamed the area between 500 000 and 100 000 years ago

- Cultural artifacts of Stone Age man have been found for the period 100 000 to 30 000 years ago.

- More than 300 archaeological sites of Stone Age man have been found

- Evidence of Bushman Folk (San) and Iron Age people from about 1500 years ago is also in great evidence.

- There are also many historical tales of the presence of Nguni people and European explorers and settlers in the Kruger area.

- There are significant archaeological ruins at Thulamela and Masorini

- There are numerous examples of San Art scattered throughout the park.

Related Download

Tourism History

- Development of Tourism

- First tourists

- First tourist facilities

- “Luxuries” – or not, for tourists

- Picnic Spots – to fence or not?

- Fees in the early days

- Retail & Catering Services

- First tourism supervisory staff

- First tourism manager

- First liquor sales to tourists

- Hotels or not?

- Supply of Fuel

- Rules and Regulations

- Automobile Association (AA) and Royal Automobile Club (RAC)

- Flights into the Park

- First roads

Development of Tourism

At the time of their proclamation, both the Sabie and Shingwedzi reserves were very poorly developed.

Only in 1916 with the appointment of the Game Reserves Commission under chairmanship of JF Ludorf, the possibility of tourism was raised for the first time in the official report of 1918. This commission, which also placed significant emphasis on the possible merging of the two reserves and to proclaim it as a national park, made it clear that the primary objective of the two reserves was the conservation of nature. The development of tourism facilities could also be considered as it would not necessarily be in conflict with the primary objective. As motivation for this point of view, emphasis was placed on the educational and research opportunities that the reserves offered, and in this respect especially the opportunity that the general public would be offered to see nature in its pristine state.

First tourists

Initially, nothing came of these recommendations, and it was only in 1923, when the South African Railways (SAR) implemented a tour to the Lowveld and bordering Maputo (then Lourenco Marques) in Mocambique, that the potential of the reserves as tourist attraction was again discussed. An overnight stop in the Sabie Reserve at the Sabie Bridge (now Skukuza) was only included in the itinerary from a convenience point of view and not because it was felt that the game would offer an attraction. It required much motivation from Stevenson-Hamilton to convince the Commissioner for Railways that the inclusion of a day excursion through the Sabie Reserve would enhance the attraction of the so-called “round-in-nine” railway excursion.

Stevenson-Hamilton’s pleas resulted in the excursion were scheduled so that the trains would travel from Komatipoort to Sabie Bridge during daylight hours. Stevenson-Hamilton arranged that a game ranger would accompany the tourists on this leg of the excursion and also overnight with them at Sabie Bridge. At Sabie Bridge there were no facilities for tourists and they slept on the train. The game ranger would brighten up the evening around large campfires while sharing interesting anecdotes with them. This arrangement was apparently very successful and it was very popular with the tourists.

At the time of the proclamation of the Kruger National Park in 1926, the idea of tourism was already established. During the first board meeting of 16 September 1926, the value of tourism as a source of revenue was also recognized. To promote tourism while simultaneously earning revenue, it was decided that a main road, with various secondary roads for game viewing would be built. The idea was that guides would be appointed to accompany the tourist, for which a fee would be payable. It was also decided that a fee would be charged for the taking of photographs. A third source of revenue would be the writing of articles which would be either offered for sale of would serve to attract foreign tourists.

The lack of accommodation facilities in the park created a significant problem. Early in 1927, the South African Railways (SAR) approached the board with the request to erect quarters and to rent it to them (SAR). Nothing came of this scheme, and in the same year, the board, through the mediation of Stevenson-Hamilton, reached agreement with the SAR to work on a joint strategy for the development of the tourism industry. The board accordingly agreed to the building of roads, rest huts and other facilities, provision of guides and protection services and to refrain from promoting independent traffic. The SAR, in exchange, undertook to provide all transport, by rail and road and to launch advertising campaigns, catering services and to pay the board a percentage of the income received.

To initiate this scheme, four two-track roads were initially provided; from Crocodile Bridge to Lower Sabie (built by CR de la Porte), from Acornhoek to the Mocambique border (via Satara), from Gravelote to Makubas Kraal (near Letaba) (latter two were built by TEBA) and White River to Pretoriuskop.

In August 1927 the board decided to open the Pretoriuskop area for tourists. This concession would however require that prospective tourists first needed to acquire a permit (which could be obtained from the secretary of the board in Pretoria, the warden at Skukuza or the game ranger at Pretoriuskop stationed at Mtimba or from White River) and tourists needed to return on the same day as no overnight facilities were provided and that only revolvers would be carried for personal protection.

The arrangement to acquire permits was confusing for many visitors and they often passed Mtimba (Post of Ranger Wolhuter) without reporting. In 1929 the Board appointed A Moodie as agent at Moodies Kloof to issue permits until 1931, when a full-time gate official, Captain M Rowland-Jones, could be appointed at Numbi Gate.

By the end of 1927 various additional proposals were considered or made by the Board in order to increase tourism traffic. The Board rejected a proposal from the SAR to build a hotel at Sabi Bridge regarding it as “unpractical”. A proposal was also presented by the SAR for the provision of suitable vehicle crossings over the Crocodile River. In turn the Board requested the SAR to open the railway bridges over the Crocodile, Sabie and Olifants Rivers for motor vehicles, to make the train service on the Selati Railway more convenient for tourists and officials of the Board, and to accept responsibility for the building of a road from Crocodile Bridge to Satara and Acornhoek.

First tourist facilities

It was only in 1928 that the provision of amenities for tourists commenced with sincerity. The first three so-called “rest huts” were built at Satara, Pretoriuskop and Skukuza (then still known as Reserve or Sabie Bridge). Simultaneously, six additional huts were also planned. These huts, or rest huts, each consisted of a set of huts or rooms with a carport. Of the six planned additional huts, nothing came of it, but in 1929 two rondavels with a radius of six metres and ten with a radius of a little more than four metres, were erected at Skukuza and two additional rondavels were built at Satara. Rest camps of the size of Skukuza were envisaged for Pretoriuskop, Satara and Letaba. Two smaller rest camps with six rondavels each were planned for Balule (then still known as Olifants Camp) and Olifants Poort (better known as Gorge) near the confluence of the Olifants and Letaba.

Construction on the rest camp at Olifants Poort already commenced in 1929. The activities were continued in all sincerity in 1930 and besides the two additional rondavels in Skukuza, four were erected at Pretoriuskop (where there were already four), fifteen at Satara, twelve at Letaba, six at Balule, one at Olifants Poort and four at Malelane. At Lower Sabie a five-bedroom guesthouse of wood and steel, which previously served as the ranger Tom Duke’s quarters, was restored and made available to tourists.

All the rondavels that were built during that time were according to the so-called “Selby” construction style (which can currently still be seen in Balule camp). Paul Selby was an American mine engineer who also served on the Board. He designed a hut with a gap between the wall and the roof and also a small hole in the top half of the original stable door. The hole in the door was meant to serve as a peephole to see if there were any dangerous animals between the huts before alighting from their rondavels – at that time the rest camps were of course not fenced. These Selby huts rapidly enticed criticism as they were too cold in winter, too dark as a result of lack of windows and also because people could peep in through the holes in the door. They also provided easy access to mosquitoes! From 1931, all new rondavels were provided with windows.

In the early thirties great progress was made with provision of additional tourist amenities. The old guest house at Lower Sabie soon proved a failure as a result of it dilapidation. It was decided to vacate it and rather build a few huts on the banks of the Crocodile River. Eight rondavels were built at Crocodile Bridge in 1931. The guest house was demolished in 1932.

In 1931 use was also made of tents for the first time. These tents, each with four beds, were initially commissioned at Skukuza and subsequently at Satara.

Besides the rest camps already mentioned, six other rest camps were established during this period. In 1931, construction was commenced at the Rabelais Gate. In 1932 the first huts in the new rest camp at Punda Maria were built. They were of the traditional wattle and daub type as cement could not be afforded at that stage. A small rest camp was also built at Malopene in 1932.

A small temporary rest camp comprising tents was erected in 1933 next to the Tsende River at Mabodhlelene. It was only in use for a few months, before construction of Shingwedzi rest camp was commenced as a replacement. Initially this camp also consisted consisted only of tents. In 1935 the first three-hut units, comprising three rooms, were completed. The roof and external wall structure of these huts as well as others built subsequently, are still in use today.

In 1932 the first ablution block – a unit with four bath and four shower cubicles – was built in Skukuza. During the same year the rest camps were fenced for the first time.

There was experimentation with a new hut design in 1935. At Skukuza, Crocodile Bridge and Letaba, the so-called Knapp- huts were erected. These were square units with corrugated steel roofs, of which the walls were built of large hollow cement bricks. These huts were not liked, they were unsightly and the erection thereof was ceased.

The last two rest camps that were opened to tourists before 1946, were Lower Sabie and Pafuri. After the closing and later demolishing of the guest house at Lower Sabie, it was decided to build a new rest camp. The first buildings of this new rest camp were designed by architects Gerard Moerdyk and were completed in 1936. This comprised three units with six bedrooms each and was laid out in a U-shape. A tent camp was opened in 1939 on the banks of the Luvhuvhu River, where the current Pafuri picnic spot is. A year later it was closed due to flooding and mosquito problems, to only be re-opened after the war.

In many ways the development of the tourism business in the Kruger Park is very similar to that of wildlife management. The Board was involved in a new and unique development for which there were no clear principles or guidelines. Decisions were initially taken haphazardly, and in many cases lessons were learnt through trail and error. As an example, when the first rest huts were built in 1928, it was not considered that rest camps would possibly be established. In 1929 when councilor Oswald Pirow pointed out that the few buildings would not at all meet the needs once visitor numbers increase, he directed as follows: that in future no new huts would be erected, but rather that areas of approximately 100 x 100 metres be fenced and that a corrugated roof structure be erected somewhere near the centre with a container providing boiling water. He felt that such a construction would meet the requirements for a rest camp as visitors preferred to camp out than to stay in huts. The Board agreed with this thinking and accepted the proposal – which was retracted in the same year.

The Boards close link with the Transport Services in establishing the tourism industry has already been reflected. In 1930 the Board undertook to build a rest camp for the SAR in the vicinity of Skukuza, once its own building program had been completed. As a result of the hectic building program, the Board could not meet this commitment and in 1931 the undertaking was withdrawn.

Notwithstanding that hot water is taken fore granted in all public facilities in rest camps today, it was certainly not the case in the early years. Only after the completion of the road between Punda Maria and Letaba, a request was tabled to the Board that ablutions in both camps needed to provide hot water. The road between the rest camps was not only very long but also dusty. (This road for most of the distance ran over dusty black peat soil and could not be graveled during construction). The then chairperson of the Board, Senator Jack Brebner, was not all pleased with the proposal and turned it down on grounds that it was just an unnecessary luxury. The discussion was continued and in 1933 it was granted with some resentment on condition that tourists would pay one shilling (10c) per bath.

“Luxuries” – or not, for tourists

In 1936 the issue of hot water for baths/shower came under discussion again when it was decided to provide such “luxury” to various other rest camps. This again led to differences in opinion and it was again reasoned that it was an unnecessary luxury, and besides that the Board did not have the funds for the required installation. The issue was again postponed and it was not until 1939 that such installations were brought about – and on condition that gents were only entitled to hot and cold showers, and that hot water for bathing for ladies was available daily between 17:00 and 21:00!

Notwithstanding the rate at which provision of tourist accommodation progressed in the early thirties, it could not meet the demand. In 1934 the SAR and the Transvaal Publicity Conference made an urgent plea to the Board to provide more accommodation. Under this pressure it was even proposed to SAR to park a number of coaches at Skukuza to serve as sleeping quarters. This proposal could not be executed as it would have been illegal.

To obtain funding for more accommodation, the South African Publicity Conference, as well as the Publicity Associations of Pretoria and Johannesburg, directed a requested to the Government in 1935 for a donation of £50,000 (R100,000) to the board for this purpose. For the expending of such an amount the addition of 150 additional beds for Pretoriuskop rest camp (with the existing 150 beds) and a new rest camp for Lower Sabie that would accommodate 200 visitors, was viewed a highest priority. Over and above these new developments, all existing huts had to be made mosquito-proof.

In August 1935 the Government announced that an amount of £30,000 (R60,000) had been approved for the development of tourist facilities. The Board decided that only R40,000 of this amount would be applied for tourism and that the other R20,000 for the provision of water sources for game. In the meantime the Board had instructed architect firms Leith and Moerdyk to prepare plans for the anticipated developments. Gordon Leith was tasked to present a design for the new Lower Sabie rest camp, while Gerhard Moerdyk had to deal with extension of Pretoriuskop rest camp as well as Malelane. By the end of 1935 the plans were already finalized, with an additional proposal that eight to ten wattle & daub huts be erected at Tshokwane. The Board accepted the latter proposal on condition that there were sufficient funds available.

The architects, as well as the executive subcommittee of the Board, had not taken account of the chairperson, Judge J de Wet. Not only did he regard the hot water for showers and baths as unnecessary luxuries, but he could not identify with extravagancies such as septic tanks, retail areas, a dining room, etc, for rest camps. According to his view, there was only a need for sleeping facilities and nothing else! The plans by Leith for Lower Sabie, were accordingly rejected on grounds that it would be too expensive, and instruction was given to Moerdyk to draw up a new – and significantly cheaper – plan.

Picnic Spots – to fence or not?

In 1938 the warden expressed his concern about picnic spots and indicating that visitors at such unprotected alighting points are subject to unnecessary dangers. The Board was of the view that as rest camps were far apart, such points were justified. After consideration of the matter, it was decided that they should be maintained, but that all picnic spots had to have a Black caretaker and that all shrubs and grass on the terrain had to be cleared. Stevenson-Hamilton was not satisfied, and in 1939 he repeated his warning. The Board maintained its position and as additional preventative measure, it was decided that in future, picnic spots would not be indicated on tourist maps and that warning signs be erected.

Fees in the early days

One of the main driving forces for the initial introduction of tourism in the Park was that it would provide a welcome source of income. With the initial opening up of the Pretoriuskop area to day visitors, the only monies that could be charged were the admission fees of £1.0.0 (R2). In 1928 the Board decided that five shillings (50c) per person would be charged at all entrances gates, with the single exception of Punda Maria- but that a minimum of R2 had to be charged per vehicle. Admission permits could be obtained from game rangers, but also from agents in White River (Legogote) and Rubbervale (of Gravelotte). During the same period visitors on the SAR “round in nine” had to pay R10 per day. This fee included the services of the game ranger.

To deter heavy vehicles from entering the Park, an admission fee for business purposes of R10 per heavy vehicle was charged.

An additional source of revenue was also offered by the pontoons over the rivers. Until the end of 1931, tickets could be bought for 50c. These tickets were valid for seven days and covered any number of crossings on the same pontoon. In 1932 tariffs were increased and vehicles were charged 25c for every time a pontoon was used. Trucks had to pay 50c. Pedestrians were required to pay 25c for the first five persons, and 5c per person above this amount.

Retail & Catering Services

To the uninformed it may today be difficult to understand why the Boards did not manage its own retail business from the early starting years. It must be kept in mind that it was exactly an acute lack of funds that limited the early development, preventing the Board from launching its own projects. This was not the only reason. When an application was submitted in 1929 to open a “tea-shop” at Pretoriuskop, it was declined on grounds that it would prejudice the “natural facilities” of the Park (whatever that may mean!).

By 1930 it was pointed out to the Board that the game rangers at Satara and Skukuza just could not attend to the administration and maintenance of the rest camps together with their other commitments. Subsequently it was suggested that contractors be appointed who would perform these duties under supervision of the game ranger. After consideration and reference of the matter by the executive committee of the Board, the suggestion was accepted. In March 1931 the contract for the management of Skukuza and Satara was awarded to P.W. Willis and, as result of increasing tourist traffic, a similar contract was awarded for Letaba in September of the same year.

The contracts that were awarded to external contractors in this manner resulted in them being responsible for the entire administration of the rest camps. This included the issuing of permits, all retail and catering, rental of bedding and even the erection of their own buildings. In November 1935, the Board decided to appoint their own camp supervisors, resulting in external contractors activities being limited to retail and catering. The first rest camp supervisors were appointed at Pretoriuskop in 1936, Skukuza and Lower Sabie.

In the early years the Board could not make much profit out of its own camps, and revenue was limited to the renting of huts. At that stage the huts were only equipped with wood and “riempie” bedsteads and any additional items such as mattresses, sheets, blankets, pillows, pillow cases, towels, etc could be hired from the contractors. Initially the renting of a hut cost one shilling (10c) per person per night. As soon as the Board provided luxuries such as hot water and the services of hut attendants, the daily tariff was increased to 25c per person.

The increase in the tariffs led to serious dissatisfaction with the visitors as it was also applicable to children under 16 years. The Board (wisely) yielded to the pressure, and the tariff for children was reduced to 10c per night. Visitors not using hut accommodation were required to pay 10c and children under 16 years 5c per day for a site (camping).

Bedding could be hired from the contractors and after vehement objections that the fee of 30c for a mattress and four blankets was extravagant, the fee was adapted as follows in 1934; a mattress would cost 5c per night, blankets and pillows 2,5c each per night. Packages were also offered, such as a mattress, blanket, pillow and pillow case at 70c per week, or even better, a complete bedding set, inclusive of sheets, for R1 per week! Only in 1940 did the Board take over the hiring out of bedding and at a nominal fee of 25c for three blankets, two sheets and two pillows per night, 15c for any additional nights and R1 per week! By then inner spring mattresses could also be hired at 20c per night.

In 1938 a proposal to the Board to hire towels – initially only at Pretoriuskop – was rejected as it would only provide a marginal income.

First tourism supervisory staff

Many problems were encountered over the years with external contractors and the tendency was that the Board would take over such responsibilities, even if such decisions were made with reluctance. After repeated complaints, the Board appointed their own rest camp supervisors in 1937 at Satara, Letaba and Punda Maria. A proposal that the Board take over all catering as a result of general dissatisfaction, was rejected. Instead it was decided to offer the catering to the SAR, but they did not see their way open to accept that.

In 1943 councilor Orpen requested that a sub committee of the Board be appointed to thoroughly investigate the retail agreements, canteen services, control over rest camps and control over tourism. The Board agreed and a year later a subcommittee was appointed. The subcommittee already recommended in 1944 that the Board take over control of all retail and catering, and that an official be appointed that would accept responsibility for all retails, catering, rest camps and tourists. Such an official had to report in a line capacity directly to Head Office (the secretary of the Board).

First tourism manager

The Board could not immediately implement the recommendation. It nevertheless led to the appointment in 1948 of the first tourism manager HC (Van) van der Veen, as well as in 1946, initiation of amendments to the National Parks Act – enabling the Board to take over all trade activities in the Kruger National Park. In 1945 the trade contract was awarded to “Kruger Park Services”, until the Board eventually took over all trade activities in 1955.

First liquor sales to tourists

An application in 1946 by the contractor to acquire a liquor license was summarily refused by the Board. It was but the first of many similar requests to the Board that fell on deaf ears – until it was eventually decided in the sixties to make liquor available to tourists.

One of issues that the Board had to attend to in the early years, was the type of accommodation to be provided as well as the layout of the rest camps. Already with the planning of the new Pretoriuskop by architect Moerdyk, more definite attention was given to the aspects such as aesthetics, and to deviate from the barracks-like outlay with huts in straight rows. The issue of the type of roofing to be used resulted in dispute amongst the Board members, with some being opposed to thatch on grounds that they offered refuse to vermin. This matter was resolved in favour of thatch roofing.

Hotels or not?

A further issue resulting in the Board “scratching its head” was that of hotels. As early as in 1927 a proposal for building a hotel at Skukuza was rejected on grounds that it would be impractical. In 1930 an application was received from Messrs Mostert and Potgieter of Johannesburg to build a hotel in the Park. This application was also declined, but merely because at that time there were no plans to build hotels in the Park.

With the high pressure on the Board to urgently provide more accommodation, an appeal was again made to erect a hotel of some 300 beds. This appeal even had the backing of The Star. The chairperson of the Board, senator Jack Brebner, was resolute in his opposition and pointed out that hotels would not be profitable as the Park would only have an ‘open’ season of six weeks per year.

In 1935 the thought of hotels even had support from the Board. Councilor Papenfus pointed out that should the Board erect its own hotels, it would be able to exercise full control over them. His proposal was supported by councilor WA Campbell, but made no impression on the chairperson and it was summarily rejected.

In 1939 a businessman by the name of Lawson enquired about the Boards position on hotels on the Park boundary and specifically whether the Board would consider making additional gates available in case of such boundary hotels. The Boards took a far more compromising position and was supportive of the principle on condition that the hotels would maintain a dignified reputation and that the Board would not suffer any losses due to tourists being lured away from the Park. As a result of these negotiations it was decided that additional gates would be provided along the Nsikazi River and at Toulon to assist Lawson. He was planning to erect two hotels, one at Plaston and the other on the farm Toulon. When Lawson requested the Board whether his guests could pay reduced admission fees on second and subsequent visits, once his hotels are in operations, the Board rejected it outright. This state of affairs resulted in the business not being viable and nothing came of these plans.

Due to lack of funds experienced during the early development years, the Board gladly accepted donations from willing private individuals and institutions. Already in 1929, Councilor WA Campbell, who was previously owner of Mala Mala on the Park boundary, donated an amount of £150 (R300) for a “rest house”. He later made more donations and one of the rondavels funded from such donations was converted to a museum currently in Skukuza rest camp.

Supply of Fuel

As a result of the location of the Park and the long distances that needed to be covered to get there, the provision of fuel was crucial from the beginning. The Vacuum Oil Company already requested the Board in 1929 to sell Pegasus petrol in the rest camps. The Board agreed to this request and by agreement the petrol would be sold at 30c a gallon (±4,5 litre) (just more than 6c a litre!), of which the Board would receive 5c. Finality of the agreement could not be achieved immediately. During this period the warden pointed out that petrol was only needed at Satara and Letaba, as ex-ranger T Duke, owner of the Bantu Shop at Skukuza, intended to also erect a petrol pump. The rest camps at Crocodile Bridge and Pretoriuskop were near enough to petrol pumps outside the Park. In the meantime Shell also applied to sell petrol in the Park.

By August 1930 Pegasus petrol was already available at Satara and Letaba. When Texas, a third oil company, also applied to sell its product, the Board decided at the end of 1930 that the product of only one company was to be sold in the Park. A final decision was not taken and the matter was referred to the executive subcommittee for further consideration. The initial decision could not be adhered to and it was decided to market only two types of petrol, Pegasus in Letaba and Satara and from 1931 also at Crocodile Bridge, while Shell Company received approval to sell its products at Skukuza and Malelane. Apparently Shell did not erect any fuel pumps at Malelane and in 1934 it was reported that Atlantic petrol was sold there and later also at Pretoriuskop, even though the request by Atlantic to sell its fuel across the park, was turned down.

Rules and Regulations

When the Park was opened to tourists in the late twenties, there were rather few rules and regulations besides that bringing in firearms were prohibited. When overnight facilities were created in the reserve, tourists were not even compelled to return to the rest camp at night. They could casually make their camp fires in the bush and then spend the night there. It soon became evident that this state of affairs would result in mischief and in November 1930 the first list of regulations, compiled for the Board, by AA Schoch, was published.

These regulations in many ways formed the base for the regulations currently in use and included, inter alia, the following: tourists were limited to rest camps at night, drives could be undertaken from half an hour before sunrise until half an hour after sunset, cars were limited to roads, a speed limit of 25 miles per hour (40km/h) was implemented, it was an offence to damage any objects and littering was also prohibited.

By 1932 it was pointed out to the Board that the regulations did not have much meaning of they could not be enforced. The Board then decided that as from 1933 a car (or motorcycle) patrol would be implemented in order to that would care of law enforcement. This idea was later abandoned as there were insufficient funds to implement the patrol service.

Automobile Association (AA) and Royal Automobile Club (RAC)

In 1932 the Automobile Association (AA) offered to station a road scout at Skukuza to undertake road patrols. The Board was obliging on condition that the AA official would not interfere with the external contractor offering a vehicle repair service at Skukuza. The AA and the external contractor could not reach a satisfactory agreement, thereby preventing the patrol service from being implemented. To counter this problem, the external contractor’s agreement was accordingly amended in 1934 resulting in the AA being able to implement its service. This service was implemented during the tourist season of 1935, with the undertaking that this would not only be an auxiliary service, but that the AA official would also assist with enforcement of the regulations.

The executive subcommittee of the Board felt so strongly about the abovementioned aspect that they even suggested that the AA approach the Department of Justice so that their official could be appointed as a special police constable.

This patrol service rapidly appeared to be a great success, and in 1936 the Royal Automobile Club also applied to implement a similar service. The application was approved and it was decided that the AA would attend to the area south of the Olifants River, while the RAC would patrol the area to the north thereof.

While the first scheduled service to the Park was only implemented during the late sixties, the Armstrong Siddeley Development Company already applied in 1930 to offer such a service. The initial application was met with approval, but when the Board requested a more formal proposal, the matter came to a halt.

Flights into the Park

In August 1930, councilor Papenfus again raised the issue of an air service. He informed the Board that he had been in contact with the Johannesburg Light Plane Club and that he was confident that a regular air service could be implemented in 1931. It was only in 1932 that the Johannesburg Aeronautical Association (previously known as the Johannesburg Light Plane Club) formally lodged an application for the introduction of such a service.

It was also proposed that such a service would be offered to Satara. The Board was concerned, especially after a report in The Star that flights over the Park would cause panic among the game. In the proposal it was emphasized that flights would not be introduced for game viewing but merely to transport tourists to the Park. It was undertaken to maintain an altitude of at least 2000 feet above ground level. The Board favourable considered the proposal. It saw this not only as a additional source of revenue, but also realized that it would be convenient in cases of emergency.

During the initial negotiations, Malelane was identified as a preferred alternative to Satara, but by June 1932, the latter was decided upon and an area 10 kilometers north of Satara was pointed out as the chosen location for the development of an air strip. It was agreed that minimum flying altitude would be 4000 feet above ground level, that the Association would develop and maintain the landing strip themselves and that they would have a contract for five years to operate the air strip. The Association also undertook to provide vehicles and staff that would take tourists on excursions. Admission fees of 50c per person would be charged and the agreement was finalized in September 1932.

It appeared that Civil Aviation did not agree that flights below 4000 feet were prohibited over the Park. It was decided that in cases of the landing strip being used for private planes, an admission fee of R10 would be charged. An agreement in the contract between the Board and the Association, stipulated that private flights would not be allowed.

In 1933 the air service was advertised as follows in a tourist guide; “In a comfortable two or three seater machine (aeroplane), the journey is accomplished over beautiful scenery, to an aerodrome six miles north of Satara, in the very heart of the KNP.

On arrival the tourists are met at the aerodrome by a roomy five-seater sedan car, and the pilot, who is well acquainted with the KNP, undertakes the dual role of chauffeur and guide.”

The first plane of the club landed during at the Mavumbye air strip during the winter season of 1933 and history was made. A total of seven planes (of which one was illegal) maintained the air service in the Park during the season. An insurmountable problem for the club was the transport of the passengers from the air strip to Satara, and this also led to the service being terminated.

After 1933 there is no mention of this undertaking. It appears as if it was never a true success and subsequently was ceased. Two air force planes used the air strip in 1934 when the locust officials of the Department of Agriculture were taken on inspection tours during the locust combating campaign. The open plains just north of the Mavumbye windmill, are all that is visible today of the former landing strip.

First roads

Up until the proclamation of the Park in 1926, the Selati railway line, ox wagons, buggy carts, pack donkeys and horses represented the only forms of transport. There were no vehicles or roads. The first tourist services introduced since 1923 by the SAR, was also exclusively limited to rail transport.

As from 1927 on, the building – actually de-bushing – of roads was started in all sincerity. Naturally, the first roads were connecting routes between established rangers’ posts. The first road to be developed, were therefore those from White River to Pretoriuskop, from Pretoriuskop via Doispane to Skukuza, from Skukuza to Satara and Crocodile Bridge, from Crocodile Bridge via Gomondwane to Lower Sabie (which was built in the mid- twenties by game ranger CR de la Porte for his own convenience, after he acquired the first motor vehicle in the Park – a model-T Ford), from Satara to Olifants Gorge (Gorge), to Letaba via Olifants River camp (Balule) and to Acornhoek, from Acornhoek to Nwanetsi, from Letaba to Gravelotte (built by WNLA), from Louis Trichardt (Makhado today) to Punda Maria and the Limpopo River (Pafuri) (built by WNLA) and from Skukuza via Salitje to Tshokwane.

In 1928, construction of the road between Skukuza to Lower Sabie was started, only to be completed in 1931. With this rapid road construction programme, a total of 386 miles (617km) of tourist roads was completed by the end of 1929. During the period 1927 to 1929, three pontoons were brought into operation, over the Crocodile River (at Crocodile Bridge), Sabie River (at Skukuza) and the Olifants River (at Balule). A so-called ‘Corduroy’ causeway was built over the Sand River at a place called “Jafuta”. In 1930, a second pontoon was introduced over the Crocodile River, at Malelane.

The road construction programme continued uninterrupted until mid thirties, and by 1934, approximately 800 miles (1200km) of roads had been completed. This included important connecting roads, such as the road between Letaba and Shingwedzi (1933) and between Malelane and Crocodile Bridge (1933).

In 1932 a new causeway was built over the Sand River to replace the old one and a causeway was also built over the Letaba River.

Although a number of new tourist roads were built between 1935 and 1946, the main focus was concentrated around maintenance and improvement of existing road network. This was made possible as a result of acquisition of a large number of road building machinery in 1938, namely two graders, two bulldozers and a tractor with trailer! Quite a lot of attention was paid to replace the pontoons, which never operated successfully, with causeways. In 1936 a causeway was completed over the Sabie River at Skukuza as well as one over the Olifants River at Balule in 1937. Construction was nearly completed on the one over the Crocodile River at Malelane. In 1938 a causeway was constructed over the Shingwedzi River, and with the completion of the causeway over the Crocodile River at Crocodile Bridge in 1945, this brought about the end of the last pontoon the Park.

The road network as it appeared in 1946, was in itself a extraordinary achievement, if the dire state of the Board finances, the shortage of equipment and manpower and the fact that the Lowveld was relatively inaccessible for vehicle traffic, is taken into account. The thinly spread game rangers were largely responsible for the building or roads as well as rest camps, and the equipment available to them were two Chevrolet trucks, which were purchased in 1929, and a single bulldozer as from 1933!

It is therefore not surprising that Board from the beginning tried all means to acquire assistance. Already in 1927, the SAR and Minister of Land were approached for financial support and the Transvaal Provincial Administration was requested to assist with the road building programme. In 1928, the Transvaal Publicity Conference lodged a strong plea that the TPA would expedite the works programme for the admission routes and causeways. It was also requested that it be adopted that the roads to the Park be used as access routes for the development of the rest of the Lowveld.

Various attempts were made in the early thirties to convince the SAR to open railway bridges to road transport. The attempts proved to be unsuccessful.

In 1935 a comprehensive development program for the Park was compiled, in anticipation of a donation that the Government was expected to make to the Board. In the plan provision was also made for dual track tar roads. The donation of R60 000 that was made, was too small to meet all the needs, and the Board approached the TPA and the Board for National Roads for assistance. When is became known in 1935 that the then Department of Defense (SA Army) required a road parallel to the eastern boundary, it was suggested that they be approached to build a tar road from Punda Maria to Crocodile Bridge.

The effort to have the roads tarred, all failed, and in 1937, the secretary of the executive committee received instruction to enquire with the University of Pretoria about a tar emulsion that could be applied in Pretoriuskop rest camp to counter the dust problem. When the chairperson of the Board, Judge de Wet, came to hear of these developments, he vehemently reacted to it and strongly objected to these so called improvements. “Are we going to keep Pretoriuskop as a rest camp or convert it to a glorified resort?” he enquired. It was not just in rest camps where dust was a problem, and councilor Papenfus argued that the dust that gathers on the plants next to the roads, could be detrimental for the game. He was therefore strongly in favour that a loan be made so that the roads can be tarred. In September 1937 councilor Papenfus’ pleas were heeded , and it was decided to proceed with the laying of tar strips on the roads between Pretoriuskop, Doispane and Skukuza and between Skukuza and Lower Sabie. This decision was not brought to fruition.

Stevenson-Hamilton remained opposed to the tarring of roads until his retirement. He expressed concern that improved roads would lead to increased speeding incidents, and that more wildlife would be killed on the roads. He felt so strongly about this that he even alleged that “….. the death toll of animals would increase beyond all bounds…”. He was not against tarred roads in rest camps.

Until the end of 1946, nothing came of any improvement to roads. Besides, there were few of the existing roads that were properly graveled. The tarring of road surfaces in the Kruger Park had to wait until August 1965 when the tarring of the Naphe Road between Pretoriuskop and Skukuza was commenced. Today there are more than 850 kilometers of tarred roads in the Park, besides 1 444 kilometers gravel roads and more than 4 200 kilometers of fire breaks.